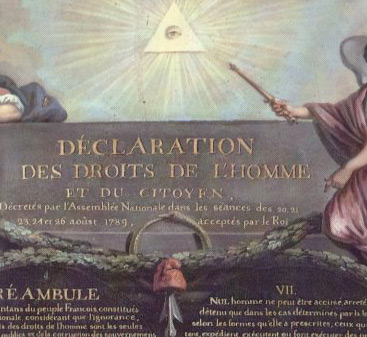

adopted by the National Assembly on August 26, 1789

Fully as significant a document in the development of democratic government as the English Bill of Rights almost exactly a century earlier, or the more recent Declaration of Independence and the still to be ratified United States Constitution, the Déclaration is different in tone from any of the Anglo-Saxon documents.The Bill of Rights, like Magna Charta, emphasises the maintenance of the traditional and eternal rights of the English people, and justifies the deposition of James II for transgressing against them. The Declaration of Indpendence, apart from its opening paragraph, in the same way as the Bill of Rights, justifies deposition of George III for the same reason. And the US Constitution concentrates on the mechanics of government: the American Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments) was still to come when this Déclaration was adopted.

The French Déclaration on the other hand concentrates, not on history, but on reason; not on the faults of the monarch but on logical arguments. In Cartesian fashion it moves from premises to conclusions, from statements of fundamental principle to their consequences. It is a political philosopher's document, not a politician's.

Les représentants du peuple français, constitués en Assemblée nationale, considérant que l'ignorance, l'oubli ou le mépris des droits de l'homme sont les seules causes des malheurs publics et de la corruption des gouvernements, ont résolu d'exposer dans une déclaration solennelle les droits naturels, inaliénables et sacrés de l'homme,

afin que cette déclaration, constamment présente à tous les membres du corps social, leur rappelle sans cesse leurs droits et leurs devoirs;

afin que les actes du pouvoir législatif et ceux du pouvoir exécutif, pouvant être à chaque instant comparés avec le but de toute institution politique, en soient plus respectés;

afin que les réclamations des citoyens, fondées désormais sur des principes simples et incontestables, tournent toujours au maintien de la constitution et au bonheur de tous.

The representatives of the French people, gathered in the National Assembly, believing that ignorance, neglect and contempt for the rights of man are the only causes of public distress and government corruption, have resolved to lay out in a solemn declaration the natural, inalienable and sacred rights of man,

in order that, constantly before all the members of the social body, it will recall to them uneasingly their rights and their duties;

in order that the actions of the legislative and executive powers, being comparable at any moment to the aims of any political institution, may therefore be all the more respected;

in order that citizens' grievances, being from now on founded on simple and incontestable principles, will lead to the maintenance of the constitution and the happiness of all.

En conséquence, l'Assemblée nationale reconnât et déclare, en présence et sous les auspices de l'Etre suprême, les droits suivants de l'homme et du citoyen.

Consequently, the National Assembly recognises and declares, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following rights of man and the citizen.

Article 1Les hommes naissent et demeurent libres et égaux en droits. Les distinctions sociales ne peuvent être fondées que sur l'utilité commune.

Men are born and live free and with equal rights. Social distinctions can only be based on the common good.

Article 2Le but de toute association politique est la conservation des droits naturels et imprescriptibles de l'homme. Ces droits sont la liberté, la propriété, la sureté et la résistance à l'oppression.

The aim of any political association is the preservation of the rights of man, which are natural and not prescribed. These rights are liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression.

Article 3Le principe de toute souveraineté réside essentiellement dans la nation; nul corps, nul individu ne peut exercer d'autorité, qui n'en émane expressément.

The basis of all sovereignty rests essentially in the nation; no body, no individual can exercise authority, unless it emanates expressly from the nation.

Article 4La liberté consiste à pouvoir faire tout ce, qui ne nuit pas à autrui: ainsi l'exercice des droits naturels de chaque homme n'a de bornes que celles, qui assurent aux autres membres de la société la joussance de ces mêmes droits. Ces bornes ne peuvent être déterminées que par la loi.

Liberty consists in being able to do anything that does not damage others; thus the exercise of the natural rights of each individual has only those limits which assure to other members of the society the enjoyment of those same rights. These limits can only be determined by the law.

Article 5La loi n'a le droit de défendre que les actions nuisibles à la société. Tout ce, qui n'est pas défendu par la loi, ne peut être empêché, et nul peut être contraint à faire ce, qu'elle n'ordonne pas.

The law has the right to forbid only actions which damage the society. Nothing which is not forbidden by law may be prevented, and no-one may be forced to do anything except that which the law lays down.

Article 6La loi est l'expression de la volonté générale. Tous les citoyens ont le droit de concourir personellement ou par leurs représentants à sa formation. Elle doit être la même pour tous, soit qu'elle protège, soit qu'elle punisse. Tous les citoyens, étant égaux à ses yeux, sont également admissibles à toutes dignités, places et emplois publics selon leur capacité et sans autre distinction que celle de leurs vertus et de leurs talents.

Law is the expression of the general will. Every citizen has the right to participate directly or through his representatives in its formulation. It must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes. All citizens, being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all public offices, positions and occupations, according to their capacity and with no other distinction than their virtues and their talents.

Article 7Nul homme ne peut être accusé, arrêté ni détenu que dans les cas déterminés par la loi et selon les formes, qu'elle a prescrites. Ceux, qui sollicitent, expédient, exécutent ou font exécuter des ordres arbitraires, doivent être punis: mais tout citoyen, appelé ou saisi en vertu de la loi, doit obéir à l'instant; il se rend coupable par la résistance.

No one may be accused, arrested or detained except in the cases and according to the forms prescribed by the law. Anyone demanding, transmitting, executing or causing to be executed arbitrary orders shall be punished: but any citizen summoned or arrested in accordance with the law must obey immediately; resistance is an offence.

Article 8La loi ne doit établir que des peines strictement et évidemment nécessaires, et nul ne peut être puni qu'en vertu d'une loi établie et promulguée antérieurement au délit et légalement appliquée.

The law may only lay down penalties that are strictly and evidently necessary, and no-one may be punished except by virtue of a law established and promulgated before the offence, and legally applied.

Article 9Tout homme étant présumé innocent jusqu'à ce, qu'il ait été déclaré coupable, s'il est jugé indispensable de l'arrêter, toute rigueur, qui ne serait pas nécessaire pour s'assurer de sa personne, doit être sévèrement réprimée par la loi.

Since all men are presumed innocent until they are found guilty, when it is found necessary to arrest someone, any force which is unnecessary to secure his person must be severely repressed by the law.

Article 10Nul ne doit être inquiété pour ses opinions, même religieuses, pourvu que leur manifestation ne trouble pas l'ordre public établi par la loi.

No-one shall be disturbed for his opinions, even religious ones, as long as their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by the law.

Article 11La libre communication des pensées et des opinions est un des droits les plus précieux de l'homme; tout citoyen peut donc parler, écrire, imprimer librement, sauf à répondre de l'abus de cette liberté dans les cas déterminés par la loi.

Free expression of thoughts and opinions is one of the most precious rights of man; any citizen may therefore speak, write and print freely, except in the case of the abuse of this freedom in cases determined by the law.

Article 12La garantie des droits de l'homme et du citoyen nécessite une force publique; cette force est donc institutée pour l'avantage de tous, et non pour l'utilité particulière de ceux, auxquels elle est confiée.

Guaranteeing the rights of man and of the citizen necessitates a public force; such a force is therefore instituted for the advantage of all, and not for the particular benefit of those to whom it is entrusted.

Article 13Pour l'entretien de la force publique et pour les dépenses d'administration une contribution commune est indispensable; elle doit être également répartie entre tous les citoyens en raison de leur facultés.

For the maintenance of the public force, and for the expenses of administration, a common contribution is indispensable; it must be equally shared among all citizens according to their means.

Article 14Tous les citoyens ont le droit de constater par eux-mêmes ou par leurs représentants la nécessité de la contribution publique, de la consentir librement, d'en suivre l'empoli et d'en déterminer la quotité, l'assiette, le recouvrement et la durée.

All citizens have the right to determine for themselves or through their representatives the necessity for public contributions, to consent freely to them, to monitor how they are expended, and to determine the way they are shared, assessed, collected and their duration.

Article 15La société a le droit de demander compte à tout agent public de son administration.

Society has the right to demand an accounting from any public agent for his adminstration.

Article 16Toute société, dans laquelle la garantie des droits n'est pas assurée, ni la séparation des pouvoirs déterminée, n'a point de constitution.

Any society in which rights are not assuredly guaranteed, and the separation of powers is not effected, has no constitution.

Article 17La propriété étant un droit inviolable et sacré, nul ne peut en être privé, si ce n'est lorsque la nécessité publique, légalement constatée, l'exige évidemment, et sous la condition d'une juste et préalable indemnité.

Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no-one may be deprived of it, except where public necessity, legally determined, clearly demands it, and subject to just and previous indemnification.

The Déclaration is a gallant attempt to lay the foundations for a liberal democracy, and it was to bear fruit in many periods of French history thereafter.

But it is flawed. In particular it is flawed by the continual raising of exceptions. Six of the fundamental guarantees (including freedom of speech, thought and religion) are subject to exceptions variously phrased but boiling down to 'except where the public interest requires'. How and by whom that public interest is defined remains unclear, but that isn't really what differentiates the system from the Anglo-Saxon tradition where rights are inalienable even when they are against the public interest (though even Magna Charta makes exception for time of war).

It is true that contemporary governments of countries otherwise in the Celtic and Anglo-Saxon tradition sometimes make, or try to make, the "public interest" superior to natural rights (as with current - mid-2000 - attempts in Britain to remove the automatic right to trial by jury), and they may have the power to do so. But they do not have the right to do so.

The argument from the public interest opens the road to tyranny, as it was shortly thereafter to do in France itself.

It is also worth looking particularly at article 3: "The basis of all sovereignty rests essentially in the nation" and article 6: "Law is the expression of the general will....". (Article 3 of Title 1 of the present French constitution repeats almost exactly article 3 of the Déclaration:

"La souveraineté nationale appartient au peuple qui l'exerce par ses représentants et par la voie d'un référendum. Aucune section du peuple ni aucun individu ne peut s'en attribuer l'exercice." - "National sovereignty belongs to the people who exercise it through their representatives and by means of a referendum. No section of the people nor any individual may arrogate its exercise".)

This concept is also foreign to both the English (in general the British) and the American traditions up to this point (and indeed in earlier French tradition), with their very deep Celtic and Germanic roots. In those traditions the law simply is. In its fundamentals it is what it is because it always has been - and no-one, not even the people, has the right to change it.

In subsequent American tradition however the French concept was shared by Jefferson and his followers: the battle which aligned the Federalists of Washington, Adams and Marshall against the Democrats of Jefferson was fought over exactly this issue.

This new element was also to prove dangerous, even more dangerous than the flaws in the American Constitution.

[ Main Contents ]